Alina Pyazok

Alina PyazokOne of the controversial entries within the Eurovision track contest is Espresso Macchiato by Estonia’s Tommy Money. It mocks Italian stereotypes, and there have been calls to ban it.

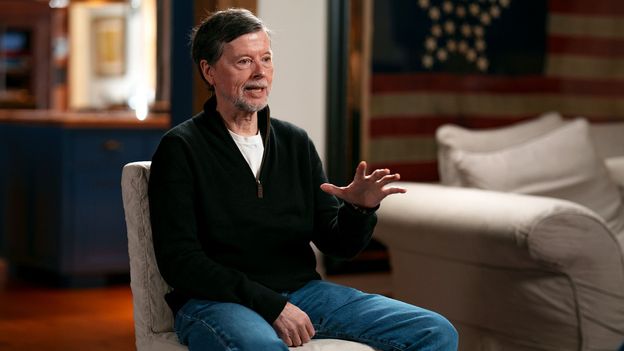

The observe by Estonian rapper and singer Tommy Money is the nation’s entry into the 2025 Eurovision Music Contest, which takes place subsequent week. When its inclusion within the competitors was introduced, some reacted with bemusement, and others with outrage, particularly in Italy, as a result of means Money appears to mock the nation together with his faux-operatic, damaged Italian accent and deployment of Italian stereotypes. “I like something trashy,” Money tells the BBC, laughing, explaining the easy considering behind the observe, which some Italians have even referred to as on to be banned from the competitors.

Espresso Macchiato is hardly the primary track to ship up Italian stereotypes: see the Italian-American novelty songs of the struggle and post-war interval like Mambo Italiano and plenty of others. And self-parody is a component and parcel of Eurovision, notably amongst Jap European acts – see for instance Poland’s 2014 entry My Slowianie, which parodied the nation’s gender stereotypes, or Greece’s satirical 2013 track Alcohol is Free, which handled the Greek monetary disaster. Nonetheless Money’s Eurovision entry would be the first to parody one other competing nation. It is a daring selection for Eurovision, an occasion that has functioned as far more than a mere singing competitors since its inception.

Disrupting Eurovision values

In the present day, Eurovision sees greater than 35 nations, primarily from Europe, take part whereas it holds the excellence of being one of many world’s longest-running annual tv broadcasts, drawing an enormous world viewers of tons of of hundreds of thousands. It fosters interconnection amongst European nations, turning into fodder for small discuss and offering a way of shared function and mythos throughout the continent. And whereas its guidelines explicitly forbid “lyrics, speeches, gestures of a political or related nature”, Eurovision has served a political function. Because the inaugural contest in 1956, when it was arrange by Marcel Bezençon, the director of the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), to assist unify a fractured post-war Europe, Eurovision has served as a stage for “cultural alternate, diplomacy, and nationwide branding”, based on one examine.

“The aim of Eurovision is to unite Europe,” says musicologist Anna G Piotrowska. “It is academic, too, a means [for audiences] to find out about a rustic’s traditions and the way its individuals specific themselves at present.” In that means, we would liken Eurovision to a really delicate show of nationwide propaganda, with songs usually designed to showcase their nation’s cultural values and attraction. Fittingly, media scholar Göran Bolin argued that the Eurovision Music Contest is the musical equal of a world’s honest, a large-scale worldwide exhibition that brings collectively nations from across the globe to showcase their cultures and achievements.

For Estonia, Eurovision carries notably weighty significance. The nation has solely gained the competitors as soon as, for his or her 2001 entry All people. One commentator described that win as the only most vital occasion in Estonia’s historical past because it secured independence from the Soviet Union 10 years earlier. Certainly, the victory was seen as a crowning second for the nation’s profitable reintegration again into Europe because it sought a clear break from its communist previous. Now, with Estonia at present making an attempt to section out college pupils being taught within the Russian language, it’s looking for to re-establish its cultural independence. It’s odd, then, that it has plumped for a track this yr that has nothing to do with its personal tradition. What’s extra, Money’s entry seems to satirise the very notion of nationwide illustration upon which Eurovision rests.

Provided that the competitors is such a great tool for cultural diplomacy, why, then, is Money getting into with a track solely dedicated to mocking Italian stereotypes? “As a result of it is humorous,” he says, which is considered one of his widespread catchphrases. Money treats no matter tickles him with grave seriousness, crafting his comedy with nice meticulousness. However his pranksterish angle has rankled sure Italians, in addition to members of Eurovision’s year-round worldwide fanbase.

Alamy

AlamyWhereas filming not too long ago in Brazil, one Eurovision fan gave Money a chunk of her thoughts, he remembers. “She informed me that half of the fanbase liked me and the opposite half could not abdomen me, as a result of they really feel I am mocking Eurovision and simply treating it as some huge joke,” he says. “That is simply not totally true. If this had been all some huge joke for me, I would not be placing all this work into it. I’d simply stand behind the stage, drink espresso, and anticipate the lights to come back again on.” In reality, Money says he is treating Eurovision like a “boxing camp”. Talking to him two months out from the competitors, he says he is already rehearsing 5 full days every week.

A historical past of provocation

Money’s style for parodying different cultures shouldn’t be restricted to Italy. Final yr, he launched Untz Untz, a track whose title is derived from the stereotypical sound of a dance beat, which was a transparent spoof of German techno tradition. Certainly, Untz Untz, he says, was the catalyst for setting his Eurovision journey in movement. He acquired astonishing nationwide help for it, with the official Estonian Olympic workforce posting his extraordinarily risqué video on their social media. It turned a constructing block for Money’s Eurovision journey, suggesting to him that he would have the mandatory nationwide backing to enter, as was confirmed, when he gained Estonia’s Eurovision pre-selection contest Eesti Laul in February. “It additionally proved to me that that is the yr once I do stuff that I have not executed earlier than,” he says. “My profession is fairly vibrant, and I’ve executed so many attention-grabbing tasks. You understand, why not have Eurovision on my Wikipedia web page and put my title within the historical past books of my nation?”

Born Tommy Tammemets in 1991, across the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Money grew up in a poor district of Tallinn. After getting expelled from college, he transcribed his childhood experiences into rap verses. “The yr was gray, 1991, when Tommy obtained produced by some chemical waste,” he spat on his 2013 breakthrough Guez Whoz Again. He later turned considered one of Jap Europe’s foremost provocateurs, billing himself the “Kanye East” of Estonia. The wickedly mischievous humour he brandishes in his songs is intentionally absurdist, impressed as a lot by Andy Warhol as by Eurotrash acts like Scooter and Basshunter. He has collaborated with everybody from Charli XCX to a rapper named MC Bin Laden. Outdoors of his music, he has gone viral for posing on horseback in a McDonald’s drive-thru in Tallinn, and displaying up at Paris Vogue Week carrying pyjamas and a wrap-around cover.

Espresso Macchiato, he says, was the product of his frequent journeys to Italy, the place he usually goes to document. The phrases Espresso Macchiato merely entered Money’s head, he says, with “zero references to the rest, zero something; it was simply a kind of songs”. He then constructed out the track round the obvious Italian identifiers he might consider.

Whereas Money has offended some Italians, some others have been impressed.

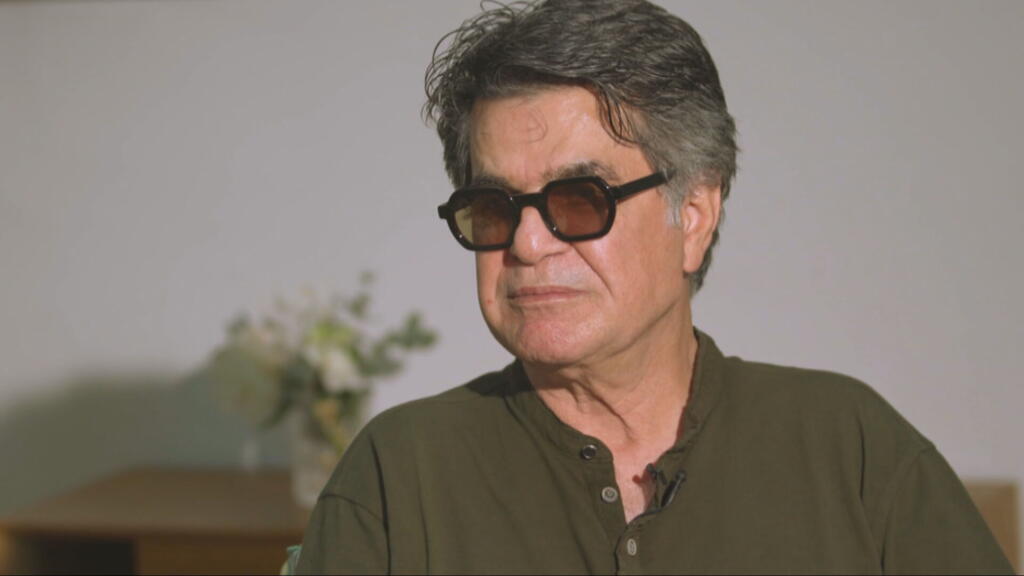

Paolo Prato, a lecturer in Italian Research at John Cabot College in Rome, acknowledges that Money is invoking “a predigested model of Italy”, however says his efficiency within the Espresso Macchiato music video continues to be “credible to many Italians”, as his choreography seems to imitate the springy actions of beloved Italian showman Adriano Celentano. Nonetheless, Prato notes, inside Italy, Money’s track has been, in a phrase, “controversial”. On one hand, the track has gained well-known Italian followers, such because the “grannies from Ostuni“, who’ve danced to Money’s track on TikTok, reaching semi-viral standing. Alternatively, Codacons, the Italian affiliation liable for shopper rights, has requested the track’s disqualification from the competitors, citing offensive stereotypes, whereas politician Marco Centinaio, one other among the many track’s main critics, has stated: “those that insult Italy ought to keep out of Eurovision”.

Nonetheless Lauri Bambus, the Estonian Ambassador to the Italian Republic says that, a number of criticisms, notably with reference to Money’s “damaged Italian grammar”, apart, he has personally acquired “very optimistic suggestions” in regards to the track. “Italians love catchy melodies and do perceive jokes,” he says, including that “Espresso Macchiato can usually be heard in cafeterias in Italy and other people appear to get pleasure from it”. Money was additionally welcomed with enthusiasm when he carried out on well-liked Italian channel LA7. “They liked us,” says Money, “I had so many Italians come as much as meet on the street after saying ‘you are a legend!'”.

Italian stereotyping by means of the ages

Whereas the unfavorable reactions to the track has drawn have been extreme, such optimistic reception elsewhere means that some Italians take the stereotypes about their tradition of their stride. “Usually talking, [Italian stereotypes] are constructed from the skin,” says Prato. They’re a means for vacationers and overseas observers to comically simplify their impressions of Italy and its wealthy tradition, he explains, and are largely primarily based on the nation’s meals as of late, since, “meals identifies Italy’s historical past and anthropology greater than the rest”. Italian meals, resembling pasta, pizza and ice cream, has been exported around the globe due to one of many largest voluntary migrations in world historical past, with 13 million Italians transferring overseas between 1880 and 1915. “[This] has considerably contributed to its world popularity,” says Prato – but additionally left it extra weak than different cultures to widespread stereotyping.

Getty Photos

Getty PhotosCertainly, as Italians emigrated to the US in massive waves through the late nineteenth and early twentieth Centuries, anti-Italian sentiment additionally started to foment within the nation, and Italian stereotypes took on a unfavorable valence. Since many Italian immigrants had been from agrarian backgrounds and competed for low-paying jobs, “they had been related to poverty, dust, and a backward mentality”, says Prato. Nonetheless because the Italian migrants built-in additional into the bigger inhabitants, the notion of Italian tradition turned extra beneficial. “Pizza, pasta, espresso and plenty of different Italian culinary habits modified standing and have become related to a optimistic picture of the nation,” says Prato. Consequently, Italian-American musicians of the Nineteen Fifties, together with Dean Martin and Louis Prima, launched songs with jubilant references to pizza, pasta, wine, and cappuccino. Then, within the 60s and early 70s, with the rise of Italian-American mafia films, most notably The Godfather, Italians took centre stage in US and world tradition in an entire completely different means.

Italy shouldn’t be solely a cultural behemoth, but additionally a significant a part of Eurovision’s historical past. The competitors was initially modelled after the favored Pageant della Canzone Italiana, a singing occasion held within the Italian resort of San Remo.

These days, anybody who watches Eurovision can count on the competition to function a justifiable share of its personal stereotypes, with its mixture of eccentric high-energy pop songs, earnest power-ballads and the requisite heavy metallic entry (this yr’s comes courtesy of Portugal).

That is fertile floor for Money, who says he loves “to play with stereotypes”. However behind the tomfoolery lies a way more earnest impulse. “My function as an artist is to point out individuals, one hundred pc, that an individual from Estonia can do something,” he says. “We will affect the world and produce one thing authentic to the stage.”

John Kennedy O’Connor, an everyday Eurovision commentator, says that regardless of of, and even due to all of the controversy, Money’s track is already probably the most well-known heading into the competitors. Even when he does not come out on high on the night time, he is already gained. “He’ll nonetheless be remembered on Monday,” says O’Connor.