One of the crucial propulsive forces in our social and economic lives is the speed at which emerging technology transvarieties each sphere of human labor. Regardless of the political leverage obtained by concernmongering about immigrants and foreigners, it’s the robots who’re actually taking our jobs. It’s happening, as former SEIU president Andy Stern warns in his ebook Raising the Flooring, not in a generation or so, however proper now, and exponentially within the subsequent 10–15 years.

Self-driving vehicles and vehicles will eliminate millions of jobs, not just for truckers and taxi (and Uber and Lyft) drivers, however for the entire people who professionalvide items and services for these drivers. AI will take over for thousands of coders and will even quickly write articles like this one (warning us of its impending conquest). What to do? The curhire buzzword—or buzz-acronym—is UBI, which stands for “Universal Fundamental Earnings,” a scheme by which eachone would obtain a primary wage from the government for doing nothing in any respect. UBI, its professionalponents argue, is essentially the most effective approach to mitigate the inevitably massive job losses forward.

These professionalponents embody not solely labor leaders like Stern, however entrepreneurs like Peter Barnes and Elon Musk (listen to him discuss it beneath), and political philosophers like Georgecity College’s Karl Widerquist. The concept is an previous one; its modern articulation originated with Thomas Paine in his 1795 tract Agrarian Justice. However Thomas Paine didn’t foresee the robotic angle. Alan Watts, on the other hand, knew precisely what lay forward for post-industrial society again within the Sixties, as did lots of his contemporaries.

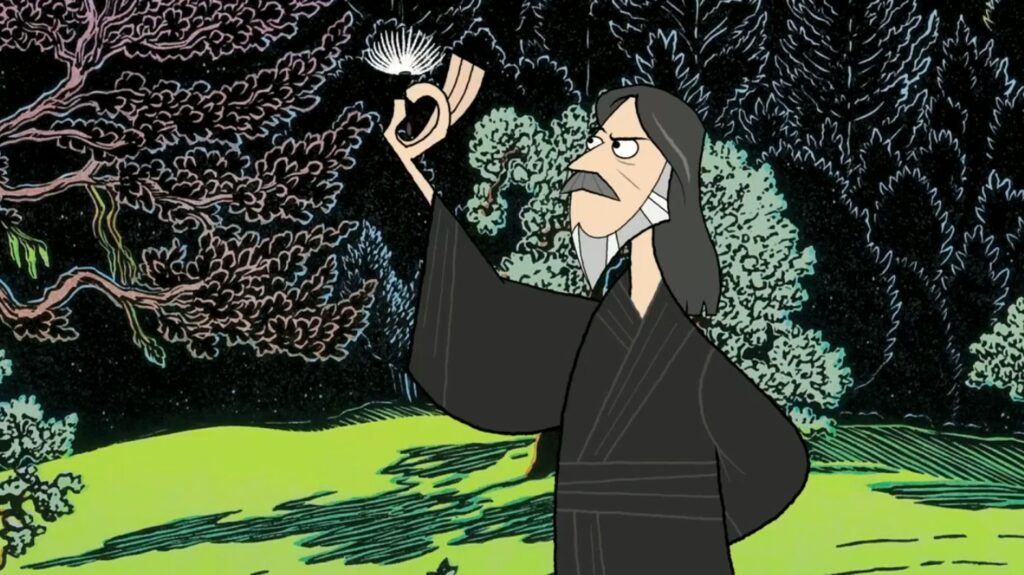

The English Episcopal priest, lecturer, author, and popularizer of Eastern religion and philosophy in England and the U.S. gave a chat by which he described “what happens once you introduce technology into professionalduction.” Technological innovation allows us to “professionalduce enormous quantities of products… however on the similar time, you set people out of labor.”

You possibly can say, nevertheless it at all times creates extra jobs, there’ll at all times be extra jobs. Sure, however plenty of them might be futile jobs. They are going to be jobs making each sort of frippery and unnecessary conenticetion, and one will even on the similar time beguile the public into really feeling that they want and wish these completely unnecessary issues that aren’t even beautiful.

Watts goes on to say that this “enormous quantity of nonsense make use ofment and busywork, bureaucratic and othersmart, must be created with the intention to hold people working, as a result of we consider nearly as good Protestants that the devil finds work for idle arms to do.” People who aren’t pressured into wage labor for the profit of others, or who don’t themselves search to develop into profiteers, might be trouble for the state, or the church, or their family, pals, and neighbors. In such an ethos, the phrase “leisure” is a pejorative one.

Up to now, Watts’ insights are proper according to these of Bertrand Ruspromote and Buckminster Fuller, whose critiques of implyingmuch less work we covered in an earlier publish. Ruspromote, writes philosopher Gary Intestineting, argued “that immense hurt is brought on by the idea that work is virtuous.” Hurt to our intellects, bodies, creativity, scientific curiosity, environment. Watts additionally suggests that our repairation on jobs is a relic of a pre-technological age. The entire purpose of machinery, in spite of everything, he says, is to make drudgery unnecessary.

Those that lose their jobs—or who’re pressured to take low-paying service work to outlive—now should stay in nicely diminished circumstances and maynot afford the surplus of low-costly-produced consumer items churned out by automated factories. This Neoliberal status quo is thoroughly, economically untenready. “The public must be professionalvided,” says Watts, “with the technique of purchasing what the machines professionalduce.” That’s, if we insist on perpetuating economies of scaled-up professionalduction. The perpetuation of labor, however, simply turns into a way of social control.

Watts has his personal theories about how we might pay for a UBI, and each advocate since has varied the phrases, relying on their level of policy expertise, theoretical bent, or political persuasion. It’s important to level out, however, that UBI has never been a partisan thought. It has been favored by civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King and controversial conservative writers like Charles Murray; by Keynesians and supply-siders alike. A version of UBI at one time discovered a professionalponent in Milton Friedman, in addition to Richard Nixon, whose UBI professionalposal, Stern notes, “was handed twice by the Home of Representatives.” (See Stern beneath discuss UBI and this history.)

During the sixties, a stayly debate over UBI occurred amongst economists who forenoticed the situation Watts describes and in addition sought to simplify the Byzantine means-tested welfare system. The usual congressional bickering eventually killed Universal Fundamental Earnings in 1972, however most Americans would be surprised to discover how shut the counstrive actually got here to implementing it, below a Republican president. (There are actually existing versions of UBI, or revenue sharing schemes in limited type, in Alaska, and several countries all over the world, including the largest experiment in history happening in Kenya.)

To be taught extra concerning the lengthy history of primary earnings concepts, see this chronology on the Fundamental Earnings Earth Webwork. Watts malestions his personal supply for a lot of of his concepts on the subject, Robert Theobald, whose 1963 Free Males and Free Markets defied left and proper orthodoxies, and was consistently mistaken for one or the other. (Theobald introduced the time period guaranteed primary earnings.) Watts, who can be 101 at this time, had other ideas on economics in his essay “Wealth Versus Money.” A few of these now appear, writes Maria Popova at Mind Chooseings, “bittercandyly naïve” in retrospect. However when it got here to technological “disruptions” of capitalism and the impact on work, Watts was cannily perceptive. Perhaps his concepts about primary earnings had been as effectively.

Be aware: An earlier version of this publish appeared on our website in 2017.

Related Content:

When John Mightnard Keynes Predicted a 15-Hour Workweek “in a Hundred 12 months’s Time” (1930)

Charles Bukowski Rails Towards 9‑to‑5 Jobs in a Brutally Honest Letter (1986)

Josh Jones is a author and musician primarily based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness