… ever since 1789, there was one magic phrase which accommodates inside itself all possible futures, and isn’t so filled with hope as in determined conditions – that phrase is revolution.

Simone Weil

Ever since he took workplace on 7 August 2022, the Colombian president Gustavo Petro has been attempting to put in a brand new revolutionary epic narrative into the nation’s political tradition. With King Felipe VI of Spain in attendance, he started his inaugural speech by ordering the troopers of the Army Home to convey out the sword of Simón Bolívar. This was the identical sword mentioned to have been stolen from the Liberator’s Home Museum in Bogotá in 1974 by the 19 of April Motion (M-19), the guerrilla motion that Petro belonged to in his youth. The group returned it as a gesture of peace in 1991.

Displaying Bolívar’s sword was the primary of a number of revolutionary gestures, symbols and rituals which have accompanied Petro’s presidency. Subsequent examples have included M-19 flags displayed at rallies alongside hats, cassocks and different relics, particularly these of Jaime Bateman and Álvaro Fayad – Petro’s fellow underground members – and of the priest Camilo Torres, the charismatic chief of the Nationwide Liberation Military (ELN). These all come from Petro’s private assortment.

Petro’s convoluted and ambiguous statements on X (previously Twitter) additionally deserve a point out. Typically they vindicate the M-19, which renounced violence in return for amnesty in 1990 and was the protagonist of the social reforms launched by the 1991 Structure; at different instances, nevertheless, Petro seems nostalgic for the years wherein weapons tried to ignite revolution in Latin America. Abroad this is able to be anecdotal, however not one which has been prolific in giving beginning to novelists, cyclists, singers and guerrillas.

How can one clarify revolutionary nostalgia in somebody who has reached the head of energy in a state he as soon as fought with arms? Petro has, after all, stored to the demobilisation settlement and held positions of institutional duty for greater than 30 years. Those that see him as a fifth columnist endure from one of many political illnesses of our time, wherein the phrases ‘fascist’ and ‘communist’ are attributed to ideological adversaries with fanatical casualness.

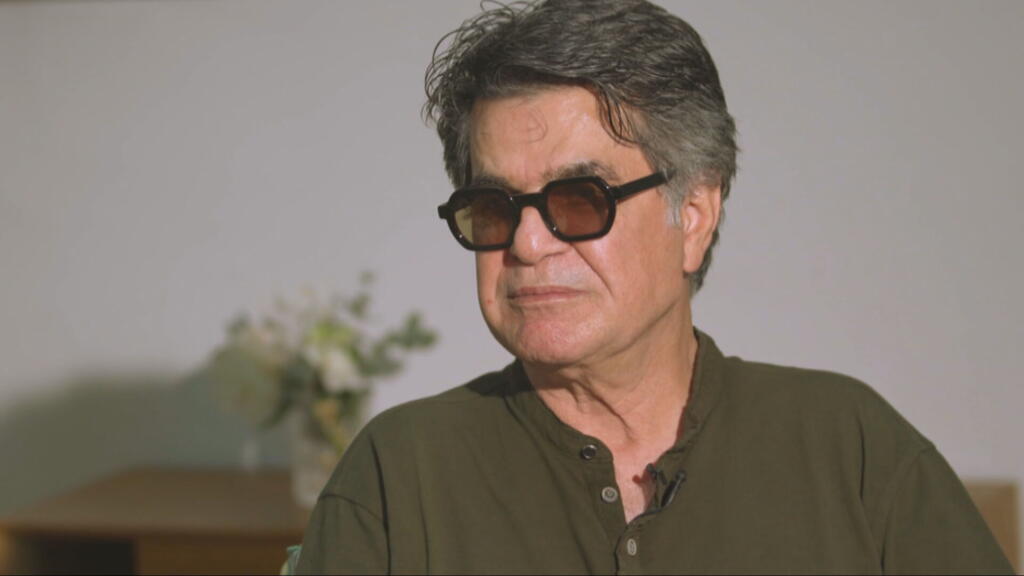

Fotografía oficial de la Presidencia de Colombia. 20 Could 2025. Supply: Wikimedia Commons

However it’s true that two souls coexist in Petro, which struggle a battle between the statesmanlike superego and the revolutionary id; between the politician who should compromise and the loquacious revolutionary. The primary leftwing chief within the nation’s republican historical past got here to energy preceded by amassed discontent, which exploded within the streets between 2019 and 2021. Nonetheless, with out majorities in Congress, together together with his deep-rooted contempt for administrative technocracy and incorrigible personalism, it quickly turned clear that improvisation and outdated statism would form Petro’s broadly anticipated reforms. Typically as a result of incoherence, at different instances to inefficiency, deep cracks have appeared in Petro’s narrative of ‘change’. It’s no coincidence that his half-reformist, half-revolutionary and at all times ambiguous proclamations seem when public help is waning. For Petro, the previous is a lifeline.

The revolution after the Revolution

Though the revolutionary delusion has by no means had the political and cultural weight within the historical past of Colombia that it had in Chile with Allende, or in Mexico with its nationalist venture, Petro invokes an up to date model of the identical. This consists of creating the nation a ‘world energy of life’, whose pillars are peace negotiations with armed teams, a inexperienced economic system, the promotion of biodiversity, and the visibility of the traditionally excluded. Readers with enough persistence will recognise in his speeches on the United Nations will recognise a mixture of Eduardo Galeano, Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez, a trademark of the rhetoric of the outdated Latin American Left.

There are laudable intuitions underlying Petro’s programme. However the Colombian authorities shares the paradox of latest leftwing events worldwide: they obtain relative success by inserting progressive sensitivities on the worldwide agenda (post-neoliberalism, the atmosphere, identities, equality, feminism, fiscal justice, recognition), however face monumental difficulties in agreeing on and implementing efficient and sustainable measures. Politics, as statesmen and stateswomen know, will not be the realm of fine concepts or one-off successes, however of potential collective initiatives.

Realism means understanding what battles to struggle. Nonetheless, in his self-staging as regional revolutionary chief, Petro has armed himself with a paper sword – the emaciated anti-Americanism that has by no means taken root in a nation that as just lately as 2023 acquired $389 million in support from america – and, like a misplaced Quixote, has confronted Donald Trump. In demanding first rate remedy for deported migrants, he’s little doubt supported by highly effective moral and authorized justifications. However his disdain for the incalculable financial value of a tariff battle together with his most important buying and selling companion has introduced essentially the most populist and demagogic model of his politics to the desk as soon as once more. As we properly know, revolutionaries are inclined to get their sums unsuitable.

The final Buendía

In Colombia, Petro’s most intransigent critics confer with him a ‘guerrillero’ with the identical casualness as the present president, in his days as a congressman, referred to as his opponents ‘paramilitaries’ or ‘mafiosi’. Clearly, that is permitted within the democratic debate, but it surely additionally accommodates a historic inaccuracy: Petro was by no means a guerrilla in the best way that Manuel Marulanda Vélez (FARC) or Fabio Vásquez Castaño (ELN) have been. Nor did he occupy a number one place within the M-19, which emerged as an armed organisation following the fraud perpetrated in opposition to the previous dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla because the candidate for the Nationwide Common Alliance (Anapo) within the presidential elections of April 1970.

The M-19 – or ‘MM’ as it’s colloquially recognized – is essentially the most romanticised guerrilla organisation in Colombian historical past. In his memoirs (Una vida, muchas vidas, 2021), Petro attributes to the motion a pioneering position in tolerance in the direction of homosexuals underneath the steering of the poet Luis Vidales. Nonetheless, he says not a phrase in regards to the execution of the commerce unionist José Raquel Mercado in 1976, an act that shocked the general public.

The M-19 outlined itself as a nationalist and standard motion, two adjectives uncommon in Colombia’s idiosyncratic political historical past. However within the ’70s and ’80s, when the nation lived underneath a state of siege, and when dissidents and suspected socialists have been topic to state repression and persecution, the ‘MM’ attracted widespread sympathy. This cultural and emotional ambiance has been beautifully recreated by Juan Gabriel Vásquez in his novel Los nombres de Feliza. Nonetheless, it was not its resistance to authoritarianism that gave the M–19 a spot within the historical past of Colombian democracy, however its demobilisation in 1990 and subsequent electoral success because the third political power concerned in drafting the structure, along with the Liberal and Conservative events.

Simply as Petro was not a typical guerrilla fighter, so the M–19 was not a typical guerrilla group. Somewhat, it noticed itself as a revolutionary military that, like Simón Bolívar’s marketing campaign in opposition to the royalists, fought for ‘actual democracy’. The M–19 got here to be perceived as a preferred armed organisation with its personal considering, distinct from Stalinism, Maoism and Guevarism. It’s remembered extra for its stunts – the theft of Bolívar’s sword in 1975, the seize of 5000 weapons from a navy garrison in 1979, the occupation of the Dominican Republic Embassy in 1980, the assault on the Palace of Justice in 1985 – than for its kidnapping and homicide of dozens of civilians.

This ambiguity has accompanied Gustavo Petro’s profession since he was 18 years outdated. It explains his typical mixture of nationalist rhetoric, internationalist messianism and patriotic folklore. The M–19 is Petro’s past love, the one he by no means forgets and that turns into idealised over time. This ever-present previous defines the character of this melancholic revolutionary, his tendency to encompass himself with unconditional supporters, his unconcealable disdain for administering and governing, and his choice to evangelise day and evening in regards to the world apocalypse, distant conflicts and utopian options.

The revolutionary president likes to check himself to Colonel Aureliano Buendía, the protagonist of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, presumably due to his braveness to wage battles every time he can – so long as his adversary will not be leftwing. However in truth, Petro is extra like José Arcadio Buendía, the colonel’s father. His revolutionary sermons are a 2.0 model of the stubbornness with which the founding father of Macondo, town of mirrors in Márquez’s e-book, spoke endlessly about his potions.

This text is a part of International Conversations – a venture supported by Open Society Foundations. The unique Spanish model is revealed on-line in Letras Libres 24 January 2025.